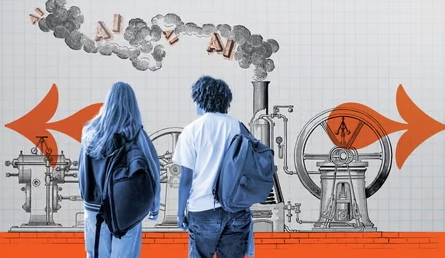

HONG KONG —For years, a degree from a top U.S. university was seen as a “golden ticket” for Chinese students, guaranteeing them top jobs back home. But today, many are discovering that geopolitics has turned their prized diplomas into red flags.

The Trump administration’s visa cancellations, later paused after a phone call between Donald Trump and Xi Jinping in mid-2019, left Chinese students in the U.S. facing deep uncertainty. At home, some graduates now find their overseas experience raising suspicion with employers, who are increasingly wary of foreign-trained talent.

Parents are paying hefty tuition bills, yet many students are asking whether the overseas gamble is still worth it, especially as China’s job market favours homegrown degrees.

Take Barry Lina, 24, from southeast China. He spent three years studying in the U.S. and dreamed of a Wall Street career until his student visa was suddenly revoked in July under restrictions targeting Chinese students with alleged military ties. He was forced to return to China, where he sent out 70 job applications but failed to make it past basic screenings.

“Maybe there’s political sensitivity,” Lina told CNN, refusing to name his Chinese university due to the sensitivity of the issue. He believes his U.S. experience has become a barrier, not a benefit.

“You feel powerless, caught between two countries’ conflict,” he said.

Foreign graduates treated with suspicion

China’s job market, both public and private, has grown skeptical of foreign-trained graduates. The number of returnees has soared, from 350,000 in 2013 to over 1 million in 2021, according to China’s Ministry of Education and the Center for China and Globalization. But enthusiasm has cooled, fueled by rising nationalism and security fears.

In April, Dong Mingzhu, chairwoman of appliance giant Gree Electric, told shareholders the company “will never hire returnees because they could be spies.” Such remarks highlight a wider distrust, especially in state-backed firms, that has left many graduates sidelined.

Since 2023, major provinces like Guangdong and Beijing have barred foreign degree holders from joining “xuandiaosheng,” a program that recruits elite graduates into government and Communist Party leadership pipelines.

A report by China’s Global Youth Summit found that nearly half of all returnees in 2023 sought government or state-owned jobs, prized for their “iron rice bowl” stability. Few succeeded.

“The public sector is becoming less welcoming to foreign graduates,” said Alfred Wu, an associate professor at Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. He linked the trend to Beijing’s heavy promotion of national security, with the Ministry of State Security regularly warning citizens that foreign spies are everywhere.

Recent state propaganda videos even dramatize stories of Chinese PhD students abroad being recruited by foreign agents to leak secrets.

Cheaper, ‘better fit’ local hires

For many employers, hiring local graduates is not just safer, it’s cheaper. “Domestic students are more cost-effective and understand the market better,” said Yuan Shen, a Shanghai-based career consultant.

She argued that many returnees who finish one-year master’s programs abroad lack strong academic or work skills compared to locals who spend years competing for graduate degrees at home.

Chinese firms also question whether Western-educated students can handle the gruelling local work culture, known as “996” 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week.

That perception hit Ezio Duan, who studied communications in the U.S. for five years. Despite sending out 400 applications, he received only three offers. He believes stereotypes about foreign graduates being less committed or capable hurt his chances.

“The benefits we thought we had six years ago have completely disappeared,” he said. “I didn’t expect this.”

A shift under Xi’s ‘inward focus’

Experts say the challenges facing students like Lian and Duan reflect President Xi Jinping’s broader push for self-reliance and control. Since removing presidential term limits in 2018 and escalating the trade war with the U.S., Xi has emphasized “internal focus” over openness.

“Xi aims for a relatively closed system,” Wu said. “The narrative is simple: China and the U.S. are adversaries.”

That shift has made foreign degrees less an asset and more a liability. For graduates who once saw themselves as symbols of China’s global openness, the ground has shifted beneath their feet.